Posted on October 13, 2025

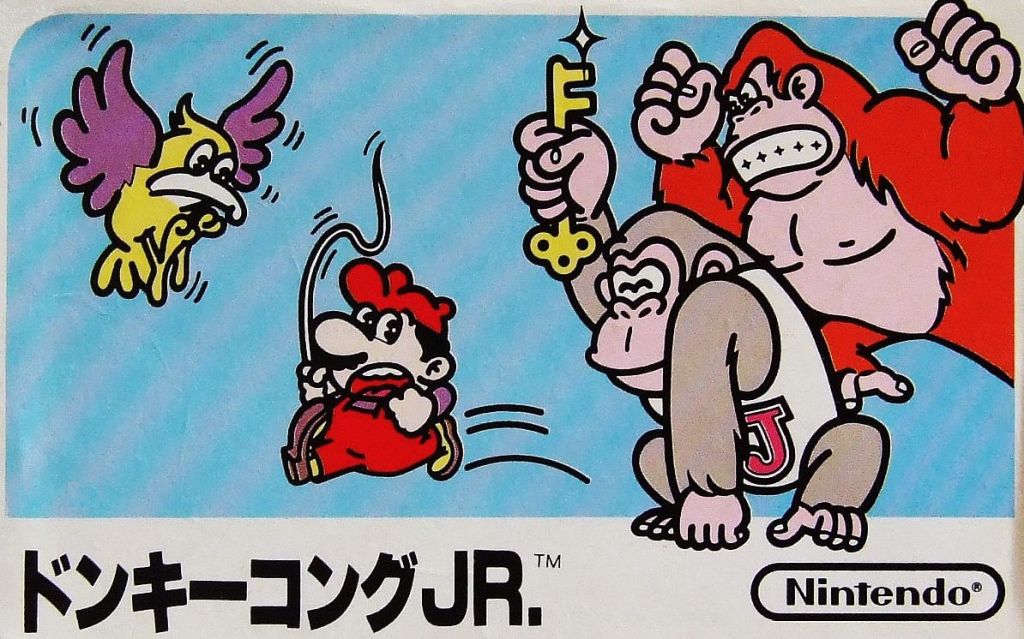

Moving on to the second of the three launch games for the Famicom, Donkey Kong Jr. which was released on July 15, 1983. This was an arcade to home conversion of the 1982 sequel to the original Donkey Kong. Where Donkey Kong could be seen as somewhat of an old game by the time of the Famicom’s release, Donkey Kong Jr. was still relatively fresh. But does that mean that it is the better game of the two? Well, let us find out.

First of all, you will notice that you no longer control Jumpman. Instead he has become the villain that put Donkey Kong in a cage! You now play Donkey Kong’s son and have to rescue your dad. Just imagine this wild and drastic change! Mario as the villain would be unthinkable today! But back then it was not a franchise, yet, so they could do whatever they wanted with it. This role reversal is pretty interesting, both in terms of story and gameplay. Because the previous game focused on jumping and on actions that a human could reasonably do. But now the game is all about an ape and his “move set”, so to speak. As such the game is centered around climbing. While Jr. can still do some jumping, most of the levels revolve around climbing. I think that this is emblematic of a certain approach to game design, that Nintendo would later be known for, i.e. revolving a game around a certain gameplay style, and then designing everything around it second.

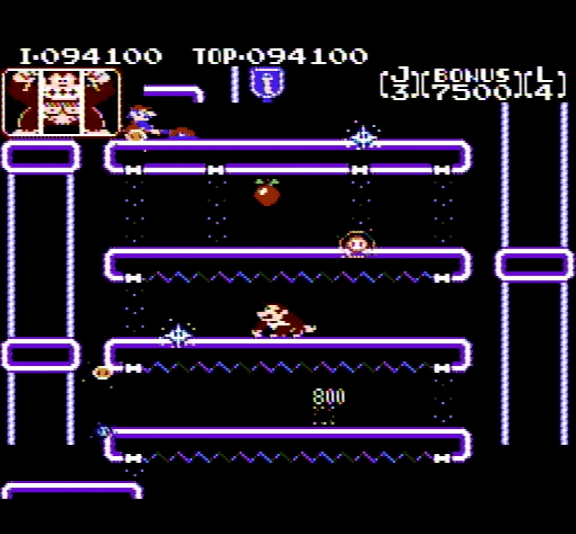

Either way, Donkey Kong Jr. plays surprisingly well on the Famicom. Climbing the vines feels much smoother than climbing ladders in the predecessor. There is no longer this awkward stiffness instead it just feels great to play! Jr. can cling to one vine or two. If he is clinging to one vine climbing becomes more difficult, but descending is done very quickly. However, if he is using two vines he can climb very fast, but descend rather slowly. This creates a very nice contrast, and a little bit of complexity. After all, if Jr. is climbing on two vines he becomes an easier target, but he can also switch easily between the left or right vine to avoid enemies coming from above or below. The levels make frequent use of Jr.’s climbing skills, and he is overall adequately equipped to deal with the challenges. Though this does not mean that it will be easy to save his father.

The game has four levels overall which come one after another in sequential order, whereas the arcade version has a similar format to Donkey Kong arcade where the first (difficulty) level/loop only has two stages, the second level three stages and so on. I think that the Famicom version does improve upon this formular by giving you all four levels one after another without this multiple loop gimmick of the arcade game. This ensures that even a mediocre player like myself can experience every single level without having to practice for many hours until I make it through the third level/loop.

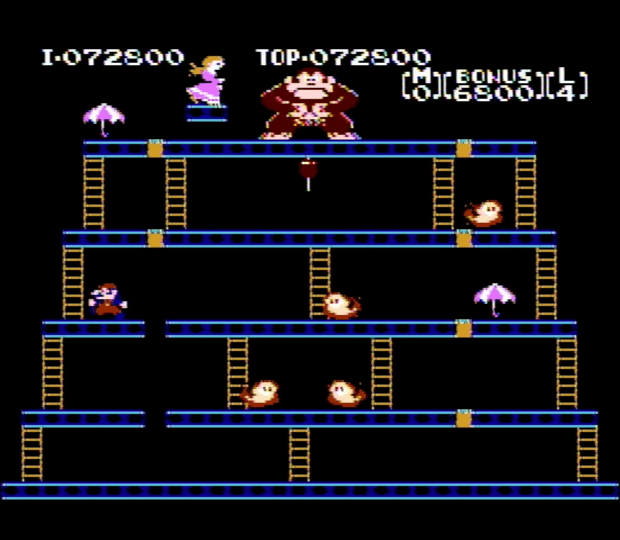

In the first stage Jr. has to climb a bunch of vines and make it from the left of the screen to the right, then up and to the goal on the upper left. Mario tries to hinder you by releasing a bunch of blue Snapjaws that move around on the upper ledge and more or less randomly pick a vine that they fall down. Apart from these endlessly respawning enemies there are a bunch of red Snapjaws that do not disappear and constantly go up and down the vines or move along the platforms. You can kill these by dropping a fruit on them and even gain some extra points this way. This first stage is not all that difficult at the beginning, but it does get somewhat challenging later on. I have also noticed that it is much easier than the arcade version since Mario can make the red Snapjaws respawn as well, on top of there just being much more enemies on the screen at once to the point that it is easy to get trapped. However, the Famicom is a lot easier throughout and you can see it right away in the first level.

Anyway, on to stage two. Here you have to have to go to the right, left, right and left again, but with some different obstacles this time around. There are now horizontally moving platforms, birds that can kill you while you are trying to make your way along the vines, and a spring. This time it does not kill you, but allows you to take a shortcut by jumping on one of the moving platform. But be careful! If you fall from too high up then you can die from fall damage. You also want to watch out for the birds that drop deadly eggs on you or this annoying handle on the left that sometimes retracts so that you can not hold onto it. Despite all of that this level is not too difficult on the Famicom version of this game.

Stage three is very different from the rest of this game. It has a futuristic theme with lots of metal and very weird sounding electronic music. This time around Mario does not send animals after you, but sparks. The blue ones drop from above and move along the metallic “vines” and the ground until they eventually disappear. Meanwhile the red ones constantly move around the platforms. Together they can pose quite a threat. You have to watch out for sparks coming towards you as well as the sparks below and above you, some of them even coming from behind. This makes the stage quite challenging as you have to keep track of everything that happens around you. You also can not jump carelessly. During early loops this stage is still quite doable, but on the higher difficulties it poses a formidable challenge.

Eventually Jr. makes it to stage four where he can finally rescue his father from Mario’s evil clutches. Here Mario and Donkey Kong are on a platform at the top with lots of metal chains hanging below it. On some of them there are weirdly looking keys that Jr. has to carry to the top thus unlocking the padlock. More so than in any previous stage Jr. has to climb a lot in this one. And by that I really mean a lot! By now you should have gotten accustomed to fast climbing with two hands and quickly sliding down on one vine/chain. Mario is now also sending two threats towards you. On the one hand are the red Snapjacks that, as you may remember, do not disappear on their own unless you kill them with a fruit. On the other hand are the birds again that respawn infinitely. They also fly back and forth this time around. Therefore you have to keep track of two types of enemy patterns at the same time while constantly getting harassed. In the arcade version this level was pure hell with something of sic to eight Snapjacks moving around as well as a constant barrage of birds. Luckily, the Famicom version just can not display so many enemies at the same time, so it becomes a lot more manageable which I personally like.

In the end, Donkey Kong Jr. saves his father only for the entire thing to repeat over and over again until you lose all your lives. It is a typical high score chaser, but a pretty good one. It is therefore perfect for occasional play sessions or maybe even more serious and dedicated attempts for a high score. I had some good fun playing this casually and just seeing how far I could make it without getting all sweaty. I even enjoyed it a little bit more than its predecessor thanks to the additional level and the more satisfying controls. It also feels like some levels have more of specific patterns that vary depending on the difficulty instead of pure randomness like the barrel stage in Donkey Kong. As such I could find more reliable ways to make my way through certain levels.

However, when I looked at my old notes from years ago when I “beat” it for the first time, I actually gave it a lower score than regular Donkey Kong. It made me wonder if I maybe just gave Donkey Kong a better score because it was the highly acclaimed original and I maybe I felt that I had to score it higher and like it more because of its reputation. Have you ever noticed how public opinion and the whole things surrounding a game made it seem better to you, like you are obligated to like it just because of its place in history or because everyone says you should and you feel wrong or weird for not feeling the same way? I kind of got this with these two games which to me highlights the difficulties of even trying to be objective about games, or media in general, where so much has already been said about it. As a result my following rating is just based on how I am feeling about this game right now.

Rating: 7.5/10

Difficulty: 2.5/10 (for the first loop, later loops would probably be closer to 5 or 6/10)

Time to beat: ca. 5 minutes (for one loop)

Beaten? – Yes. Multiple loops, but no maxed out score or kill screen.

Ranking: #1 (of 2)

Next time we will look at the final launch game for the Famicom: Popeye. Stay tuned for that!